by Antonia Crane

My mom’s aggressive cancer returned the same week I got into an MFA program for writing— a terrible idea considering the recession of 2008. Mom insisted I “Get that degree!” so I enrolled even though I had no way to pay for it. I’d lost my personal assistant job, and my sugar-daddy-once-removed, a stout, Mexican man who was missing part of his thumb, suddenly disappeared for good.

A few weeks into grad school, I drove up the California coast to Humboldt where redwoods cast long shadows and the icy ocean raged silently while I euthanized my mother. I immediately plunged back into sex work. There’s no pamphlet on how to keep showing up for class when your favorite person dies. It’s like waking up without arms or feet. I floated in the fog of her absence and I wrote about her frail limbs and her moans of pain when I took her off the morphine for a few hours those final days. I wrote about her peeing the bed. Spilling milk on the floor. Choking on water. I wrote about her writing her own obituary and her cobalt blue vases filled with her orange azaleas. I wrote about meeting men in motels off the 405 to jack them off—how I was usually one hand job away from being homeless. I wrote about my mom’s feeding tube and her pastel fuzzy socks I slid off her feet before they took her body away. In my mind and on the page, my mom’s dying body merged with mine going through the motions of sex work. I couldn’t separate the two because they were braided in my mind. I kept Cheryl Strayed’s essay “The Love of My Life” (The Sun, # 321) close at hand because it gave me permission to write about my specific raging body grief and how I hurled my pussy at the world and dared it to keep me safe.

I met my fellow writers and Antioch Alums Patrick O’Neil, Seth Fischer and Melissa Chadburn in cafes around Los Angeles, and whenever I wrote the scene about euthanizing my mom, I cried into my latte. They didn’t mind. Whenever I am writing about the hardest stuff, the knife digs deep and I’m finally getting somewhere worthy in my writing: a place where risk runs wild and free: a place of despairing and transcendent connection.

Now I get to teach writing to students at UCLA where I trick them into writing the hardest things too.

After we play a silly alliteration name-game, the first thing I ask my students at UCLA to do is write down three things they are most afraid to write about. The room crackles with their collective fear and anger that I should be so forward and ask this of them so soon after learning all of their names.

“Don’t worry, you won’t be reading this out loud,” I say.

Their nervous eyes soften. Then I tell them they will be writing about that thing in my class over the next few weeks. Why? Because they are about to make fear their dance partner and I am going to show them some dance moves.

As a lifer dancer—tap, ballet, modern and then decades in strip clubs across America, dancing is my habitat. I’ve learned that my interest in writing, music and dance is its ability to transmit emotion. The way to do that is to get on the floor and expose my belly—undulate with quivering beats of desire and shame in order to get down with my fellows. In writing I conquer my deepest fears by writing about the most embarrassing things like masturbating to escape my overbearing brother or throwing up Zingers when I binged at the grocery store where I swept the floor with a giant heavy wooden broom on weekend visitations at my Dad’s. Emotional taboos are a good place to begin any story because it’s the hot terrain of risk.

Begin with writing about your family.

Which brings me to one of the hardest things to write about and my favorite thing to write about: Sex. Holy fuck. Writers are afraid to write about sex because we are afraid to look stupid and small. But sex writing is a great character reveal: it shows how shy and ecstatic and tender a person is—or how clumsy, drunken and jealous a lover is. It exposes the grim thrill of a back alley dumpster fucking and that our beastly aggressions are just childish desires amplified. I enjoy pushing my students to write about sex because when two people are naked together, there is risk.

Writing is motherfucking hard. To be brave enough to see things clearly amidst distraction, denial and low self-esteem and then illuminate the truth on the page is difficult. Showing our vile, selfish, cruel, cowardly, joyful humanity takes more than just balls. It takes boobs, brains and heart. And it takes hours and hours of writing shitty drafts for me to write anything worthwhile.

But no one comes to a non-fiction writing class because things are going well.

We come to writing because we contain vulnerability, rage, shame, madness, shattering insecurity and desolate loneliness. We write in order to let our dragons rise—give voice to our most savage selves, most embarrassing desires, most awkward sex and our bone crushing losses. My students write about what is troubling them—their wolves at the door, urgently knocking on their hearts. They write about sexual abuse, divorce, missing siblings, accidents, robberies and lots and lots of death. And they learn to hear the music of great writers until they can hear their own and dance on the page.

Why does difficult material make great stories? Most of the things I yammer on about while teaching I have ruthlessly stolen from my professors and colleagues, Cheryl Strayed and Steve Almond. Things like: “Put yourself in the company of your wild, intuitive creativity” and “Make yourself available to the work,” “Write with humility and guts” and “Write with Love” and “Let it Rip.” My hope is to share the wisdom they have shown me to others and to urge young writers to write about that thing that is punching holes in their heart—that’s where the music is.

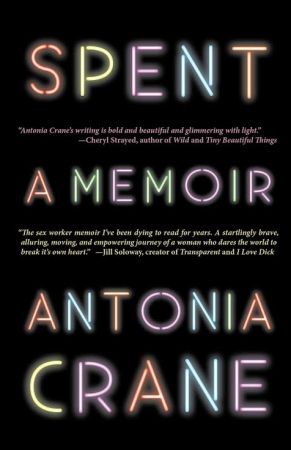

Antonia Crane is a writer, Moth Slam winner, and writing instructor in Los Angeles. She is the author of the memoir, Spent (Barnacle Books, Rare Bird, 2014). She has written for The New York Times, Quartz: Atlantic Media, The Toast, Playboy, Cosmopolitan, Salon, The Believer, The Rumpus, Buzzfeed, Electric Literature, DAME, PrimeMind and lots of other places. Her screenplay, “The Lusty” co-written with Silas Howard about the Exotic Dancers Union is a recipient of the San Francisco Film Society/ Kenneth Rainin Foundation Screenwriter’s Grant, 2015. She is at work on an essay collection and a memoir.

is a writer, Moth Slam winner, and writing instructor in Los Angeles. She is the author of the memoir, Spent (Barnacle Books, Rare Bird, 2014). She has written for The New York Times, Quartz: Atlantic Media, The Toast, Playboy, Cosmopolitan, Salon, The Believer, The Rumpus, Buzzfeed, Electric Literature, DAME, PrimeMind and lots of other places. Her screenplay, “The Lusty” co-written with Silas Howard about the Exotic Dancers Union is a recipient of the San Francisco Film Society/ Kenneth Rainin Foundation Screenwriter’s Grant, 2015. She is at work on an essay collection and a memoir.