by Cassandra Lane

“The thesis of A Room of One’s Own—women must have money and privacy in order to write with genius—is inevitably connected to questions of class,” Mary Gordon wrote in a 1981 forward to the book that comprises Virginia Woolf’s famous extended essay.

I read the book in early 2001, highlighting Woolf’s self-assured sentences in bright orange ink and writing in the margins with fervent scrawls. As an African-American woman who grew up poor yet still believed I had stories to tell, a voice that needed to be shared, and who desired, more than anything, to tell stories with brilliance, I certainly took issue with parts of Woolf’s argument. Whereas she insisted that one write calmly and without bringing attention to the self, my heart raged against social injustice; I wrote in first person. I was not wealthy or emotionally detached enough to be the kind of writer she described.

Still, the book had a profound effect on me, and I subscribed wholeheartedly to the belief that with time and privacy a determined woman could create brilliantly. I was married to a man who was married to his career as a photojournalist. He understood when I decided to quit my job as a newspaper reporter to pursue writing books.

Having decided not to have children, Ric and I pledged to treat our creative work as our offspring. We would not be bogged down by the cares of parenthood; instead, we would capture and share powerful stories that impacted children—whether in the housing projects of New Orleans or the shanty towns of South Africa.

In late 2001, we left New Orleans and moved to Los Angeles, where Ric took a job at the local Associated Press and I enrolled in a two-year MFA program, worked on my first full-length manuscript and dissected books.

We transformed our apartment around our creative endeavors, choosing to sleep in the living room on a futon that I covered in printed pillows and textiles during the day. Ric used the single bedroom as an office and dark room. My office sat off the kitchen, taking over what would have been the breakfast nook. Built-in bookcases and crannies surrounded the cozy corner. I kept the French windows open to welcome the scent of cumin wafting from my elderly Armenian neighbors’ kitchens.

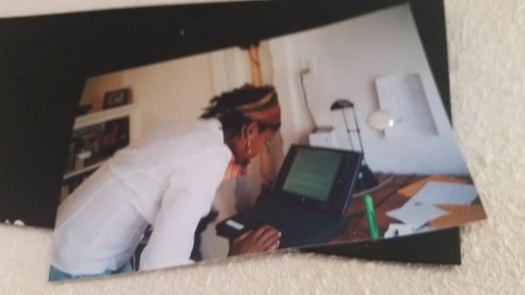

I still have a photo that Ric took of me back then: I am standing, but bent over my laptop, squinting at the screen. My right fingers are on the keyboard, my left fingers pressed against my mouth. I am engrossed in revising a chapter that is about to be published. My desk is littered with notes, highlighters and my eyeglasses. Taped to the wall above the desk are handwritten passages that I planned to work into the larger story.

All was right in the creative world back then. Or so it appeared. In reality, I was deeply torn. Living off my savings, Ric’s paychecks, and the bit of change I brought in from selling antiquarian books, I worried daily about money, about my financial dependence. And while we had made so many sacrifices to commit to our creative work, I was not satisfied. Ric and I spent long hours apart (including a month of vacation time he used to work on a self-funded project in South Africa). A romantic at heart (and a fool), I complained bitterly. When I was at my lowest, I plopped down in the plush, cream-colored rocking chair I bought as one of my first pieces of furniture after college. Instead of rocking and reading, I would sit there and think and sulk, overcome with loneliness.

What I wish I had realized is that this thing that I thought was loneliness was exactly where I needed to surrender. I should have walked into that blackness and discovered its glory. Instead, I squandered my time, creating drama in my life instead of on the page. I graduated from the MFA program and started teaching at a high school for students who were on probation. This job seemed to fill me as I funneled my creative energy into my students. My dreams (or so I believed) began to change. I yearned, all of a sudden, to have my own child.

A few years after moving to California, Ric and I divorced. We’re still good friends, but our lives have taken wildly different turns. He eventually quit his AP job and moved to Peru, then Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda, making ends meet by freelancing while pursuing his larger projects. I got remarried—to a divorced man with two adolescent boys. We also had a child together—Solomon, who is now eight.

I can almost hear Virginia Woolf scoffing at my choices. In addition to arguing that women need money and privacy in order to access their brilliance, Woolf insisted that women were historically poor because they were enmeshed in childbearing, child-rearing and housekeeping.

As the eldest of my single mother’s five children, I swore at 16 not to have children because I, too, equated child-rearing with poverty and the relinquishing of one’s dreams. It is true: mothering does not, on the surface, support the writing life. Add to that the necessity to work full-time so that one is not “poor,” and there goes another chunk of time and space that bars one from the page.

Yet while I could sit and lament that I am not independently wealthy and that my time is not always my own, I decided last year to fight against the sense of doom that Woolf paints, as well as against my own pessimism. I started writing and submitting more than I had the previous year. I launched a monthly writing workshop, began going to literary readings again.

I told my husband: “I need a room of my own.”

Last summer, I attended the A Room of Her Own Writing Retreat in New Mexico, where I met one lovely woman writer after another, many of them mothers. It was encouraging to me when Maxine Hong Kingston offered a rebuttal to the idea that one must have privacy to write. “I did not have a room of my own,” she said. Instead, she wrote amidst the hustle and bustle of her family.

Even with this piece of encouragement, this reminder that no excuse should keep us from writing, I daydreamed of the house that my husband and I were in the middle of buying when I left town. It was a small 1920s bungalow, but the selling point for me was the converted, detached garage that sat at the rear of the backyard. While I no longer had all the time in the world, I could create a special space for my thoughts and words. When I returned to L.A., we closed escrow, and I mapped out a design for my writing space.

Previous owners had fully converted the once two-car garage, turning it into a rental unit with its own kitchenette, half-bath, track lighting and heating system.

To bring in more natural light, my husband had our contractor knock out part of a wall and install a sliding glass door. I hung olive-gold drapes and sheers that tango with the wind when the patio door is open. Our contractor also pulled up the room’s dingy navy-blue carpet and replaced it with flooring that looks like roasted walnuts.

I stocked the kitchenette with teas, a hot plate, a tea kettle and brightly potted succulents. I lined the room with books—in cases, on floors, on tables— and graced the walls with art, including street scenes from my beloved New Orleans, photos of friends, postcards, a “beyond resolutions” mural, and a gorgeous goldenrod tapestry that a friend brought back from Hungary.

Rounding out the design: an oversized wooden chair that I call The Reading Throne, my writing desk, a huge rustic armoire (it holds three towering stacks of journals), two small couches, a coffee table, wooden carvings, a thick rug and floor pillows.

“It’s like a bed-and-breakfast, boutique hotel, retreat and gallery all in one,” my friend Ramona said as she sat on the rug during one of our recent writing workshops. I have also welcomed my former A Room of Her Own roommate into my space. Six months after our New Mexico retreat, Charu left her family and work in Maine to write, sleep, drink tea and meditate in my studio for a weekend. Ryane, a writer friend and mother who lives a mere five minutes away, came over one afternoon to write an essay that was just published. More writers are on their way.

I am overjoyed about my space, and of what it is turning out to be for others.

Still, and oddly, there are nights and early mornings when I don’t want to go back there. I am drawn to the warmth of my son’s and husband’s bodies, the sound of their breathing, the way the weight of them settles a room. Out back, I sometimes sense a certain hollowness in the quiet, a lightness that feels as though the whole room might float away. The key, I am learning, is to acknowledge this moment and let it pass. To ground myself, I light an incense and a candle. Put the kettle on to boil. Turn on my laptop. These sounds, sights and scents begin to stir what wants to be awakened, and I get to work.

A few tips for creating a Room of Your Own

- If you are in the process of buying or renting a new home that you must share, try to hold out for one that includes a space that could be carved out for you. Even if there’s no “she-shed” on the premises, perhaps you can convert a great walk-in closet or breakfast nook or garage.

- Talk to the other people in your house about how sacred this space is to you. They must respect it, honor it, and ask that visitors do the same. They cannot, for example, offer your space as a guest quarters without your consent.

- Put you in the room: relics, awards, degrees, mementos that mark your story. Make a sign and hang it out front: Delia’s Den or Sand’s Studio or Carla’s Creative Lab. When we name a thing, it is free to become.

- Even if you are squeezed for time, try to visit your space every day. A full hour is ideal, but on days when you can only carve out 30 minutes (or five) go into your room and sit, breathe, pray, give thanks. Write a paragraph, a line. All of it is sustenance. And when you have to leave, fret not. Recall your special place. Envision yourself in there, raising a character you created to new heights or unpacking a memory that haunts you. Your room is waiting for you, as patient as an old tree.

Cassandra Lane is a former newspaper journalist and teacher who has published essays, columns and articles in The Times-Picayune, The Source, TheScreamOnline, BET Magazine, The Atlanta Journal Constitution, Bellingham Review and Gambit, and in the anthologies Everything but the Burden and Daddy, Can I Tell You Something. She is an alumna of Voices of Our Nation Arts (VONA) and A Room of Her Own Writing Retreat (AROHO). Her essay, “Familiar Fruit,” will be published in the anthology Ms. Aligned later this month. She has performed readings at the Tennessee Williams Literary Festival, Beyond Baroque, AROHO and more. She received an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles. A Louisiana native, she now lives with her family in Los Angeles.

Cassandra Lane is a former newspaper journalist and teacher who has published essays, columns and articles in The Times-Picayune, The Source, TheScreamOnline, BET Magazine, The Atlanta Journal Constitution, Bellingham Review and Gambit, and in the anthologies Everything but the Burden and Daddy, Can I Tell You Something. She is an alumna of Voices of Our Nation Arts (VONA) and A Room of Her Own Writing Retreat (AROHO). Her essay, “Familiar Fruit,” will be published in the anthology Ms. Aligned later this month. She has performed readings at the Tennessee Williams Literary Festival, Beyond Baroque, AROHO and more. She received an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles. A Louisiana native, she now lives with her family in Los Angeles.